Revisiting the Distribution of Letters in Afan Oromo after 30 Years

by

Demessie G Yahii, PhD

Introduction

Thirty years ago, the Journal of Oromo Studies published a seminal paper titled “Distribution of Letters in Oromiffa Text” [1]. Over the past three decades, Afan Oromo has experienced significant growth in the standardization of orthography, expansion of vocabulary, and refinement of writing styles. This article aims to explore the evolving statistical distribution of letters in Afan Oromo, providing an updated analysis of the results presented in the original paper.

The initial two introductory sections of the original article remain pertinent today, and readers are encouraged to refer to those sections, as the full article is easily accessible alongside this one. This contribution focuses exclusively on the “data collection and analysis” sections, maintaining similar section titles for convenient comparison.

Data Collection and Results

In contrast to the limitations of print-only resources for Afan Oromo publications in 1994, today’s landscape offers a wealth of easily accessible online materials. This shift is particularly noteworthy considering that, in 1994, the Internet was in its infancy, and Afan Oromo’s use of the Qubee Alphabet was just over two years old.

Given the abundance of online publications, our data collection process benefitted from a diverse range of sources. Where available, we selected up to 10 articles each from various Afan Oromo online publications listed below, with total word counts as shown.

| Afan Oromo online source | articles count | word count |

|---|---|---|

| Adda Bilisummaa Oomoo | 10 | 13,299 |

| Addis Standard Afaan Oromo | 10 | 7,232 |

| Ayyaantuu News Afaan Oromoo | 1 | 3,372 |

| BBC News Afaan Oromoo | 10 | 5,944 |

| Gadaa Journal, Jimma University | 10 | 41,317 |

| VOA Afaan Oromoo | 10 | 2,669 |

| CUMULATIVE TOTAL | 51 | 73,833 |

Table 1: Afan Oromo textual data sources

The initial data collection for the first article relied exclusively on transcribing printed material into electronic form. As a consequence, raw data preprocessing was inherently intertwined with the transcription process. With the advent of online media, a noticeable variation has emerged, particularly in the casual deployment of different characters to represent the glottal stop, known as “hudhaa” in Afan Oromo.

Originally, the apostrophe (‘) served as the designated character for hudhaa. However, word processors like Microsoft Word introduced the “right single quotation mark” as an additional choice, primarily for its aesthetic appeal. The accessibility of similar characters in online environments has introduced a new challenge, leading to confusion in some publications due to the improper interchange of these characters.

Referring to Table 2, it becomes evident that only two characters are suitable for representing the glottal stop: the apostrophe (‘) and the right single quotation mark (’). The use of other characters as quotation marks for hudhaa introduces unnecessary complexity to the Afan Oromo orthography.

| character | ordinary name | Unicode (decimal) | orthography usage comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| " | double quotation mark | U+0022 (34) | Not for hudhaa! Use for quotes only. |

| ' | apostrophe or single quotation mark | U+0027 (39) | Use for hudhaa. Also use for single quotes. |

| ` | grave accent or backtick | U+0060 (96) | Avoid in Afan Oromo! Used as diacritical mark in other languages. |

| ‘ | left single quotation mark | U+2018 (8216) | Use as single quote with the right counterpart. |

| ’ | right single quotation mark | U+2019 (8217) | Use for hudhaa. Also, use as single quote with the left counterpart. |

| “ | left double quotation mark | U+201C (8220) | Use as double quote with the right counterpart |

| ” | right double quotation mark | U+201CD (8221) | Use as double quote with the leftcounterpart |

„ | right double low-9 quotation mark | U+201CE (8222) | Use as "curly" double quotation mark with left counterpart. |

| ‟ | left double low-9 quotation mark | U+201CF (8223) | Use as "curly" double quotation mark with right counterpart. |

Table 2: different quotation mark characters with usage comments

To enhance the reliability of our statistical analysis, we performed some pre-processing steps on the raw textual data including correcting typos, removal of abbreviations and foreign words, and other extraneous information not related to the textual content.

As an aside, notable observations surfaced with regard to how the glottal stop character was used. This aspect of the correction was therefore particularly important.

- BBC NEWS Afaan Oromoo: An intriguing inconsistency was identified in the use of double contiguous apostrophes (”) in lieu of a single double quotation mark (“) without a clear rationale. Additionally, a peculiar choice was noted where two consecutive right-single-quotes were employed instead of a right-double quote, as exemplified in instances such as: https://www.bbc.com/afaanoromoo/articles/c992x5424wzo. Furthermore, the usage becomes even more unconventional with a combination of less common quote marks, for instance, ‘’haleellaa tasaan’’ – https://www.bbc.com/afaanoromoo/articles/cv27jl10n3jo.

- Gadaa Journal at Jimma University: the right-double-quotation-mark (”) is consistently utilized in lieu of apostrophes or right-single-quotes throughout the majority of the content.

- It is noteworthy that, with respect to other sources: Adda Bilisummaa Oromoo, Addis Standard Afaan Oromoo, Ayyaantuu News Afaan Oromoo, and VOA Afaan Oromoo, there was a commendable adherence to conventional orthographic rules, demonstrating an accuracy rate approaching 100% in their application.

Results and Observations

Table 3 provides a concise summary of the average percentage of letters and the presence of the glottal stop character in the Afan Oromo text, aligning with the corresponding data in Table 4 from the 1994 article.

| Letter | Frequency (%) | Letter | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 24.1 | N | 6.5 |

| B | 2.7 | O | 5.6 |

| C | 0.9 | P | 0.1 |

| D | 3.3 | Q | 0.9 |

| E | 6.2 | R | 4.1 |

| F | 2.5 | S | 3.8 |

| G | 1.9 | T | 4.7 |

| H * | 3.2 (4.0) | U | 5.7 |

| I | 9.3 | V | 0.0 |

| J | 1.3 | W | 1.1 |

| K | 3.3 | X | 0.3 |

| L | 2.5 | Y | 1.4 |

| M | 4.0 | Z | 0.0 |

| ' | 0.8 |

Table 3: Distribution of letters in Afan Oromo text

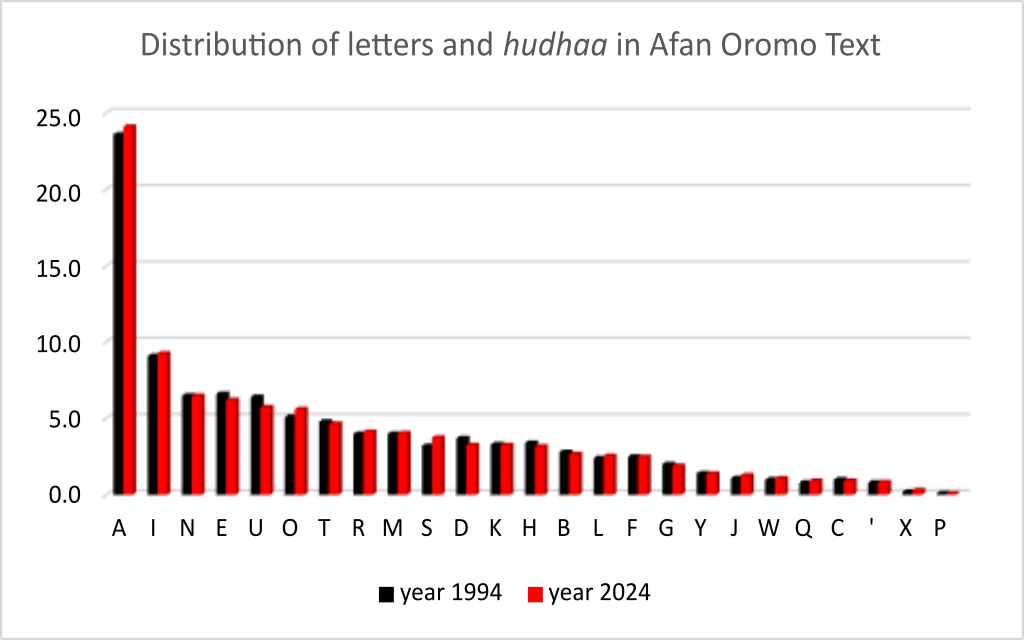

The alignment of these two sets of results is visually demonstrated in Figure 1, indicating a robust consistency over a 30-year span. Given the language’s inherent stability, the enduring distribution of letters defining linguistic attributes is expected. Minor variations may be attributed to vocabulary expansion, shifts in writing styles, or accounted for as margin of errors.

Figure 1: Comparison of year 2024 vs. 1994 of % letters distribution in descending order.

Both dominant vowels and consonants maintain their established ranking order (A, I, E, U, O for vowels; N, T, R, M for consonants). Notably, the consonant S supersedes D in the ranking, prompting inquiry into whether this is a statistical anomaly or if writing style and vocabulary growth contribute to such shifts—an aspect that merits exploration by social linguists.

With a robust data sample, we confidently assert that the reported results not only align with historical findings but also offer a highly descriptive portrayal of Afan Oromo. This analysis enables a definitive identification of dominant vowels (A) and consonants (N) characterizing the language, in stark contrast to the English language, where E and T hold such prominence.

A Playful Diversion

Let’s indulge in some linguistic amusement! By selecting five consonant letters to complement the vowels, we concoct the whimsical world of AIEUO, dwindling from a majestic 24% to a modest 5.6%, and NTRMS, gracefully descending from 6.5% to an understated 3.75%. To all word-game enthusiasts, we extend an invitation to craft mnemonic phrases or sentences that align with these seemingly mysterious 5-letter abbreviations—AIEUO and NTRMS. May the lexical creativity flow! Best of luck in the linguistic labyrinth.

A Thankyou to Our Data Sources

Staying on the subject of data analysis and results, it is fitting to express our gratitude to the sources of our data, whose cooperation brought immense satisfaction to our work. Special thanks are extended to the online publishers mentioned in Table 1 for granting permission to utilize their Afan Oromo content in this analysis. The accessibility of their materials has been instrumental in simplifying our research process, and we genuinely appreciate their valuable contribution.

Conclusions

In the span of three decades, Afan Oromo has undergone remarkable growth, marked by a rapid expansion of its vocabulary and the continual refinement of writing styles. In the context of this article, certain aspects of orthography warrant consideration and recommendation. Orthography, encompassing spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and other visual elements of language in written form, is a critical component of effective communication.

While Afan Oromo’s phonetic algorithm simplifies spelling, this article specifically addresses the glottal stop punctuation. Further recommendations will be explored in a subsequent article, focusing on the punctuation of postposition terms and word contractions to ensure consistency and clarity in written communication.

Regarding the glottal stop, writers are strongly encouraged to use either the apostrophe character or, alternatively, the right-single quotation mark. The utilization of other quotation marks introduces unnecessary complexity to Afan Oromo orthography and is strongly discouraged. Neglecting this guideline can have notable consequences for text processing tasks, including spelling checks, translations, text-to-speech processing, and other emerging applications involving Artificial Intelligence (AI). This establishes the foundational Afan Oromo orthographic set as the 26-letter alphabet, plus the apostrophe or right-single quotation mark for the glottal stop. This is what is referred to as the Latin-based Qubee Alphabet. Other quotation and punctuation marks should be employed as intended, similar to English language writing conventions.

In the 1994 article, a suggestion was put forth to discontinue the use of hudhaa in favour of an alternative solution. Regrettably, this proposal did not receive the expected support. While there is a discernible inclination towards moving away from hudhaa, the momentum for this shift is not substantial. The limited adoption might be attributed to the insufficient presentation of evidence and the benefits associated with the alternative solution at that time.

With a more rigorous analysis and comprehensive data supporting the proposed solution in the current study, the recommendation will be revisited and explored in a follow-up article. Ceasing the use of hudhaa holds promise for enhancing the consistency and clarity of written text, a topic that will be delved into in future studies.

Facebook Comments