The Power of Afan Oromo Qubee: from Transliteration to Generating Amharic Text

by

D Girma, PhD

Introduction

Qubee is the Afan Oromo system of writing based on the Latin alphabet. Introduced over three decades ago in 1991 for formal education, it has experienced rapid growth, contributing to significant advancements in broader areas such as education, linguistics, literature, and both printed and digital media. For detailed information on the Qubee orthography, readers are encouraged to refer to references [1] and [2].

One prominent feature of the Qubee writing system is its reliance on phonetic writing. In simple terms, words are transcribed as they are pronounced in the native Afan Oromo language, ensuring a clear and unambiguous pronunciation of the written word. This orthographic property proves to be a powerful tool for transliteration—the process of converting text from one script into another, preserving the original pronunciation while using characters from a different script.

For example, the text “Qubee yeAmaarinyaa nibaabin lemetsaf yiiredal.” represents the transliteration of Amharic text: ቁቤ የአማርኛ ንባብን ለመፃፍ ይረዳል። In this case, transliteration occurs by employing the Qubee phonetic system for writing. This is feasible because the unambiguous nature of phonetic writing allows for the representation of words from any given language in phonetics, as long as the phonetics of the transliterated language are available in the host language.

This article provides an in-depth exploration of the foundational concepts behind achieving transliteration and script generation through phonetic writing. Subsequently, it introduces a practical implementation in the form of a software tool called Q2A—an application available for download on the Google Play app store. Emphasizing the algorithmic robustness of the Qubee writing system, the article underscores its evolution into a content generation tool, with the potential to extend its application to various other languages.

Transliteration to Native Script—A Linguistics Detour

If a transliterated language permits, it is also feasible to convert the transliterated text into a native script for that language. For this to occur, a transliterated language should facilitate the mapping of transliterated phonetics to unambiguous orthography or a written representation.

Although no formal proof is provided, the concept can be easily understood through examples. Therefore, consider the following as an axiomatic statement.

On the other hand, the Amharic system of writing exhibits a several-to-one or S2O mapping of {T => O}. For instance, consider the frequently cited dual pronunciation of the Amharic word አለ, leading to the mapping {(ale, alle) => አለ}. Here, (ale, alle) represents Qubee phonetic transliterations of the Amharic words: አለ (he said) and አለ (there is or there exists), both converging to a single orthographic representation. Thus, the S2O mapping defines the Amharic writing system.

As a side note, the English writing system is characterized by a several-to-several or S2S mapping. This arises from its inclusion of homophones, where the same-sounding words have different spellings, as exemplified by {tu => (to, two, too)}, and homographs, featuring the same spelling but different sounds, as seen in the mapping {(miinet, maynuut) => minute}. The English language, in fact, encompasses several homographs, including words like bow, lead, tear, and tire, to name a few.

To ensure completeness, it is essential to state that, for transliteration, the writing system must adhere to the O2O mapping, as demonstrated by the Qubee writing system. The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) serves as one standardized system of phonetic notation designed to represent the sounds of a diverse array of spoken languages. Therefore, IPA should fulfil the O2O mapping with a much richer set of phonetics than Qubee can accommodate. It is noteworthy that IPA is a purpose-built writing tool designed to cater to several languages worldwide and is not an inherent part of any specific language, as is the case with Qubee.

Many languages, such as Spanish, Italian, Finnish, Korean, etc., employ a phonetic writing system. While recognizing this fact, it is beyond the scope of this article to digress and analyse to what extent these languages satisfy the O2O mapping. Contextualizing the discussion within the Qubee versus Amharic writing— the focus of this article—renders such a digression irrelevant.

Why Phonetic Writing in the First Place

While providing this overview of the linguistic detour, it is appropriate to comment on why phonetic writing was the chosen path for Afan Oromo. This discussion may serve to dispel some of the misunderstandings surrounding the use of Qubee phonetic writing in the first place.

It is well recognized that (1) tonal characteristics (pitch variation) and (2) phonemic length variations in a language can influence the difficulty of learning and mastering pronunciation. This is due to the introduction of an additional layer of linguistic complexity for the learner brought about by tonal and phonemic length variations.

Tonal languages, such as Mandarin and Cantonese Chinese, Vietnamese, and Thai, among others, can alter the meanings of words based on the pitch or tone in which a syllable is pronounced. For instance, Vietnamese has six distinct tones, while Thai has five. These tonal languages utilize pitch variations to convey different meanings, emphasizing the significance of tonal distinctions in their phonetic systems.

In contrast, Afan Oromo and Amharic are non-tonal languages, but they exhibit the second aspect of phonemic length variations. In the case of Amharic, this is exemplified by the dual pronunciation of the word አለ, with the variation attributed to phonemic length.

In Afan Oromo, phonemic length variations are highly prevalent, as illustrated in the example below. Within the framework of Qubee phonetic writing, we can characterize phonemic length variation as a matrix of short/long vowels versus soft/hard consonants. In linguistic terms, the soft/hard consonants are referred to as lenis (soft) and fortis (hard), resulting in the following matrix:

(lenis, fortis) × (short, long) Matrix

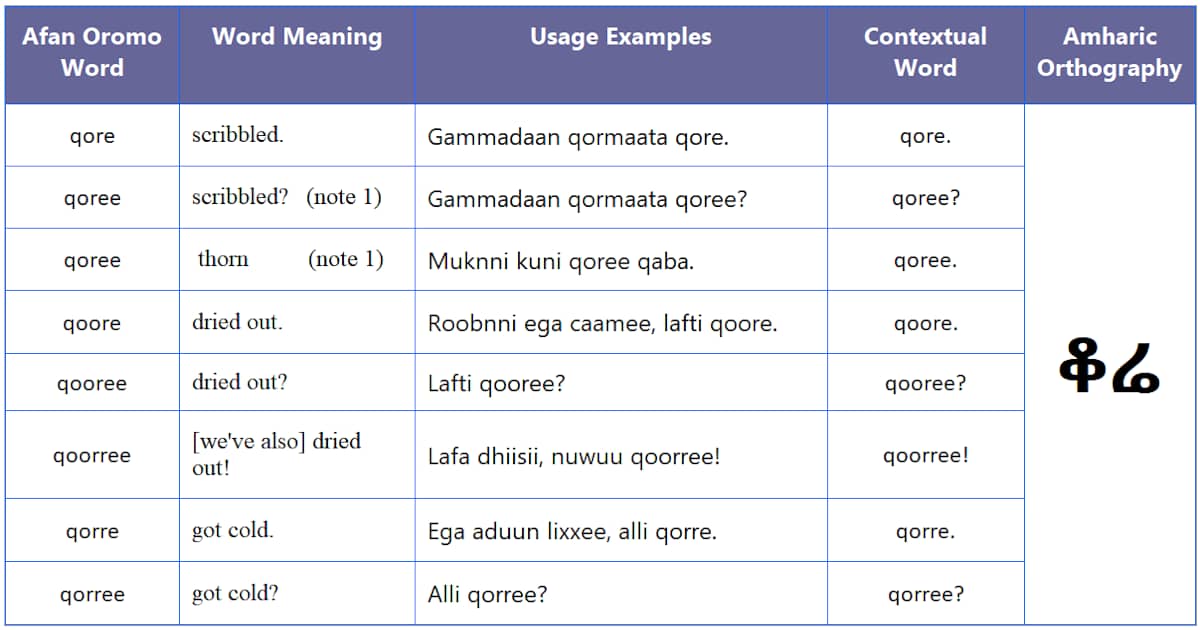

This linguistic property is also applicable to Amharic, although not as widespread as in Afan Oromo. In fact, it is the prevalence of phonemic length variations in Afan Oromo that necessitates the use of phonetic writing. This can be easily understood through the several-to-one (S2O) mapping of Amharic orthography ቆሬ from various Afan Oromo words, as illustrated in the Table below.

Observe the phonetic words that map to the Amharic orthography ቆሬ. Now, readers should be able to appreciate the role of phonetic writing in disambiguating multiple Afan Oromo words. In this example, there are as many as eight Afan Oromo words, all represented by a single Amharic orthography ቆሬ.

Table 1: Illustration of several Afan Oromo words with phonemic length variation versus single Amharic orthography.

Note 1 (from Table above): This illustrates a good example of a slight tonal difference for the word qoree. Although Afan Oromo is a non-tonal language, a negligibly small tonal variation can be observed, particularly in interrogative sentences. It might be tempting to write the interrogative version as qoreee (with three e’s, and why not?) to disambiguate it from qoree (meaning thorn). This is a case of a tiny percentage where phonetic representation may be incomplete but can still be easily mitigated.

The passage vividly illustrates the challenges faced by non-Amharic speakers when decoding the non-phonetic writing of Amharic. The variability in pronunciation based on phonemic nuances makes it essential to have a prerequisite knowledge of the language to accurately decipher and pronounce words. This situation places non-Amharic speakers at a significant disadvantage.

An intriguing example from a flower shop further emphasizes the intricacies of Amharic pronunciation. The word ይገባሻል! displayed across a captivating rose picture on the wall presents a puzzle for non-Amharic speakers. Through mental decoding, the author interprets it as “yiggebbashal!”—conveying the message of “you deserve it!” to the recipient of a rose flower, cleverly employed as a familiar marketing tactic.

The author reflects on the challenges encountered during elementary education, attempting to pronounce words accurately without a complete grasp of the language. Even for Amharic speakers, the challenge persists if they lack the context to decipher the intended meaning. Is it “yiggebbashal!” or “yigebashal!”? The latter leads to a word maze with subtly different meanings, which is left to the reader to explore.

Phonetic writing, as exemplified by “yiggebbashal!”, alleviates such complications by firmly tying pronunciation to the intended word. In this way, one doesn’t need to be an Amharic speaker to pronounce it correctly, highlighting the efficiency of phonetic writing in overcoming these linguistic challenges.

Implementation of Amharic Transliteration and Script Generation

Central to the transliteration and generation of Amharic script is the phonetic algorithm embedded in the Afan Oromo Qubee writing system. In the context of transliteration into Amharic, the Qubee phonetic system offers a precise O2O mapping algorithm that can be easily translated into a computer program. During transliteration and script generation, the operation may appear as if one is using a keyboard for Amharic text. However, it is not an ordinary keyboard; the input keyboard is, in fact, based on Latin letters as the user edits the Qubee phonetic text to generate the Amharic text.

How it all started:

It was the summer of 2019 when I reached out to a friend—an avid blogger and commentator on Facebook—to inquire about the keyboard app he used for writing in Amharic. While most of his writings were in Afan Oromo and English, I noticed occasional posts in Amharic to reach a wider audience. He suggested an Amharic keyboard app, which I installed and tried out. Unfortunately, the experience didn’t bring me joy.

Wearing the hat of a software developer and well-acquainted with the phonetic algorithm as the unique feature of the Afan Oromo Qubee writing system, I was convinced there could be a better and quicker way to write Amharic text using the familiar Latin keyboard. The non-ambiguous phonetic algorithm embedded in the Qubee writing as discussed above, made it suitable for a straightforward computer code implementation.

In a matter of days, this conviction led to the birth of the Q2A app, with the acronym denoting—yes, you guessed it—”Qubee to Amharic”. The app was made available on Google Play and Microsoft app stores as far back as 2019. Now, with the Multiplatform Application User Interface (MAUI) being my preferred development framework [3] , I’ve upgraded the Q2A app with a fresh look and feel. This journey has also motivated me to pen down this article, which, along with the two previous ones [1], [2], thoroughly documents various facets of Computational Linguistics as applied to Qubee.

You can install the Q2A app from Google Play app store by clicking or tapping here.

Conclusions

The inception of my journey was sparked by a straightforward desire: the ease of writing in Amharic. This quest resulted in the development of the Q2A app, unlocking the potential of Qubee. Today, individuals equipped with a smartphone and basic typing skills can effortlessly engage in “Qubee to Amharic” writing.

Having embarked on a linguistic detour, we’ve sought to elucidate why phonetic writing is imperative for Afan Oromo. The pervasive phonemic variations, vividly illustrated through a real example, aim to persuade readers that phonetic writing serves as a crucial tool in alleviating the linguistic complexities that could otherwise significantly hinder the pace of learning in both the written and spoken aspects of Afan Oromo.

The foundation of phonetic writing sets the stage for Qubee’s O2O or one-to-one mapping between sounds and letters. This transparent logic enables the development of an algorithm capable of accurately translating phonetic Qubee text into script. Picture it as a smart keyboard attuned to the inherent sounds of both languages, seamlessly bridging the gap between phonetics and script.

This marks merely the initial phase. As technology advances, the potential of Qubee continues to broaden. Envision voice-to-text translation or automated content generation, driven by the straightforward elegance of phonetic writing. The prospects for transliterating other languages appear increasingly promising, owing much to the innovative spirit encapsulated by Qubee.

It is important to note that, in its present state, Q2A functions as a modest productivity tool rather than a robust word-processing application. Its primary focus lies in generating concise text snippets, easily transferable to various applications such as messaging platforms. The Q2A app offers users the flexibility to store up to 10 snippets, and while this number is arbitrary, it can be adjusted to accommodate 100 or more, providing enhanced versatility.

Despite the current intentional limitations of the Q2A app, there’s no inherent reason for these constraints to endure. Leveraging the same phonetic algorithms, it is entirely feasible to develop a heavyweight content processing and word-processing application that caters to diverse languages..

Q2A also serves as a testament to how languages can coexist harmoniously, enabling both to flourish in the technological era. Qubee has matured to facilitate Amharic writing, illustrating the potential for linguistic harmony. This reflection brought to mind Dr Andargachew Tsige’s recent suggestion to replace Qubee with the Amharic script for Afan Oromo. However, it is crucial to dismiss such thoughts, as Qubee writing holds immense potential, not only for Afan Oromo but also for Amharic, and potentially numerous other languages that remain unexplored.

Postscript:

By sheer coincidence, as I have been authoring this article, news reports have surfaced about certain individuals at universities proposing unwarranted changes to the Qubee writing system, including altering its name. At least two digital channels have extensively covered this matter, providing clarity on the ongoing situation. I am deeply appreciative of their efforts.

Needless to say, I have been disheartened by these developments, and I take this opportunity to express my humble opinion regarding the Qubee writing system:

- Hands off Qubee! Qubee is here to stay and has the potential for further refinement.

- Consider the memories embedded in Qubee, from its inception, credited to many personalities, to its implementation under the auspices of the Ministry of Education in 1991, under very daunting working conditions day and night to get Qubee to the classrooms. How could someone propose changing the name when Qubee encapsulates the history of numerous memories?

- The Qubee phonetic writing adeptly meets the demands of Afan Oromo. Any minor shortcomings, estimated to be less than 1%, can be addressed through incremental improvements. In my own attempt to transliterate Amharic text, I found it necessary to introduce additional phonemes not originally present in Qubee to accurately represent Amharic sounds. An example of this is the introduction of unique Amharic phonemes such as ቧ, ሷ, ጯ, created by incorporating a vowel digraph ua, as seen with word-sounds like bua, sua, cua. This exemplifies the incremental improvements mentioned earlier. As outlined in the built-in help for the Q2A app, users will discover the inclusion of new consonant digraphs specifically designed to accommodate Amharic phonetics. This dynamic adaptation showcases the ongoing expansion of Qubee’s phonetic representation to encompass the nuances of different languages.

- Direct your efforts towards incremental improvements through research articles instead of attempting to reinvent that round thing! To provide an example, the issue with words like “hodhee” can be mitigated simply by doubling the consonant, resulting in “hoddhee”. Similarly, the tonal aspect of “qoree,” as mentioned above, can be addressed by using a triple vowel. There’s nothing to shy away from when considering such solutions, especially given that these are very rare cases.

- Let me further illustrate incremental improvements that can enhance the brilliance of Qubee. As indicated in references [1] and [2], the apostrophe or “hudhaa” can be eliminated. This removal introduces numerous flexibilities and new opportunities that enrich the orthography of Qubee, which cannot be thoroughly discussed here. Additionally, the introduction of diacritics to compact vowels presents a possibility for reducing overall text. It’s important to note that this need not affect user-based writing but can be implemented during post-processing of already written text for print and display presentations. In short, the future looks bright for Qubee!

References:

- Demessie G. Yahii, “Revisiting the Distribution of Letters in Afan Oromo after 30 Years“, Journal of Afan Oromo, January 1, 2024.

- Demessie G. Yahii, “Distribution of Letters in Oromiffa Text“, The Journal of Oromo Studies, Volume 1, Number 2, Winter 1994, pp. 66-71.

- Demessie Girma, “Taming the Microsoft .NET MAUI Beast for Multiplatform App Development“, published at the LinkedIn Professional Network, December 21, 2023.

Facebook Comments